Eating Disorders and Males

Eating disorders are serious, complex mental illnesses accompanied by physical and mental health complications which may be severe and life threatening. They are characterised by disturbances in behaviours, thoughts and feelings towards body weight and shape, and/or food and eating.

Eating disorders are diagnosed based on associated symptoms and behaviours, how often these occur, and how long they have occurred for. For more information on eating disorder diagnoses, check out the NEDC fact sheets.

Eating disorders can affect people of any gender. There has been an under representation of males in eating disorder research (1), and research with males is almost exclusively with cisgender males and may not be inclusive of people who identify as trans or gender diverse.

Prevalence of eating disorders

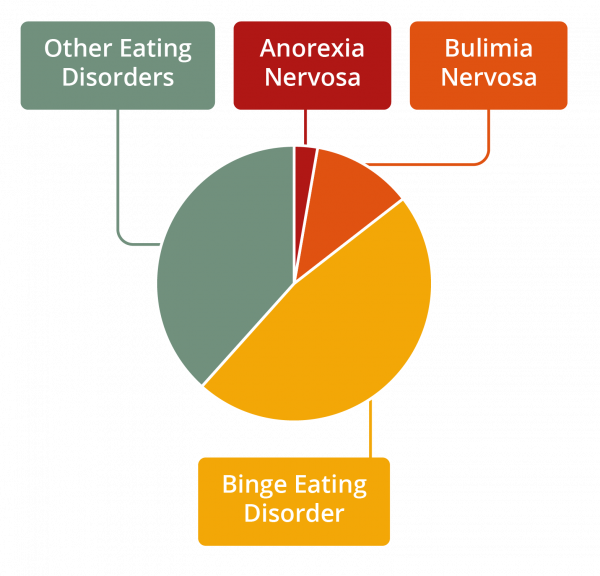

Any person, at any stage of their life, can experience an eating disorder. More than one million Australians are currently living with an eating disorder (2). Of people with living with an eating disorder, 3% have anorexia nervosa, 12% bulimia nervosa, 47% binge eating disorder and 38% other eating disorders* (2).

Emerging research suggests that people who identify as trans, gender non-binary or gender diverse are at two to four times greater risk of eating disorder symptoms or disordered eating behaviours than their cisgender counterparts (3-6).

Figure 1. Prevalence of eating disorders by diagnosis

*Other Eating Disorders includes all other eating disorder diagnoses excluding anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.

It is estimated that one third of people reporting eating disorder behaviours in the community are male (7). Males account for approximately 20% of people with anorexia nervosa, 30% of people with bulimia nervosa, 43% of people with binge eating disorder, 55-77% of people with other specified feeding or eating disorder (8) and 67% of people with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (9). The prevalence of males living with an eating disorder may be much higher and under-reporting may be related to underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis and the stigma associated with eating disorders (10).

Research on the perceived barriers towards help-seeking for people with eating disorders found that stigma and shame were most frequently identified as barriers for accessing treatment (11). Males may experience stigma associated with the common misconception that eating disorders are a ‘female’ disorder which may present as a barrier to seeking and engaging in treatment (12,13).

Development of eating disorders in males

The elements that contribute to the development of an eating disorder are complex, and involve a range of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Any person, at any stage of their life, is at risk of developing an eating disorder.

Some of the triggers and high-risk groups, presentations and communities that may put males at an increased risk of developing an eating disorder include:

• Direct or perceived pressure to change appearance or weight

• Influence and pressure of the media and social media

• External and internal pressure to adhere to the ‘thin ideal’, ‘ muscularity ideal’ or ‘fit ideal’

• Belonging to LGBTQIA+ communities

• Experiencing body dissatisfaction, negative body image and/or distorted body image

• Fasting or restriction of food intake for any reason

• Medical conditions which impact eating, weight and shape (e.g. type 1 and type 2 diabetes, coeliac disease, post-surgery)

• Mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety)

• Engaging in competitive occupations, sports, performing arts and activities that emphasise body weight/shape requirements (e.g., dancing, modelling, athletics, wrestling, boxing, horse riding)

• The childhood and adolescent developmental periods

Warning signs of eating disorders in males

Warning signs of an eating disorder can be physical, psychological and behavioural. It is possible for someone living with an eating disorder to display a combination of symptoms, or no obvious symptoms. Eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours in males may present differently than females, particularly with muscularity-oriented disordered eating (14). However, the warning signs of an eating disorder can occur across all genders.

Physical

• Sudden weight loss, gain or fluctuation

• In children and adolescents, unexplained decrease in growth curve of body mass index (BMI) percentiles

• Inability to maintain normal body weight for age and height, failure to grow as expected

• Change in physical appearance (e.g., increased muscle bulk)

• Signs of vomiting such as swollen cheeks or jawline, calluses on knuckles or damaged teeth

• Fatigue (e.g., always feeling tired, unable to take part in normal activities)

• Bloating, constipation, or the development of food intolerances

• Compromised immune system (e.g., getting sick more often)

• Fainting or dizziness

• Lowered testosterone

• Sensitivity to the cold

Psychological

• Preoccupation with body shape, weight and appearance (e.g., focus on fitness, muscle toning and/or weightlifting, pursuit of leanness and muscularity)

• Preoccupation with food or with activities relating to food

• Body dissatisfaction or negative body image

• Distorted body image (believing the body looks different than it does)

• Heightened sensitivity to comments or criticism (real or perceived) about body shape or weight, eating or exercise habits

• Low self-esteem and feelings of shame, self-loathing or guilt

• Heightened anxiety or irritability around mealtimes

• Depression, anxiety, self-harm or suicidality

• ‘Black and white’ and ‘perfectionistic’ thinking - rigid thoughts about food being ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and holding unrelenting high standards around food, body weight shape/appearance and or physical activity

Behavioural

• Compulsive or excessive exercising (e.g., exercising when injured or unwell, becoming distressed when unable to exercise)

• Repetitive dieting behaviour (e.g., counting calories, skipping meals, fasting, avoidance of certain foods or food groups, intermittent fasting)

• Patterns or obsessive rituals around food, food preparation and eating (e.g., inflexible eating regime, sudden interest in meal planning, preparation and food shopping, reading nutritional labels)

• Changes in food preferences (e.g., refusing to eat certain foods, claiming to dislike foods previously enjoyed, bringing own food to social events)

• Evidence of binge eating (e.g., disappearance or hoarding of food)

• Misuse of supplements and/or use of anabolic steroids, or any other performance or image-enhancing drugs

• Evidence of vomiting or misuse of laxatives, appetite suppressants, enemas and/or diuretics

• Frequent trips to the bathroom during or shortly after meals

• Social withdrawal or isolation from friends and family

• Secretive behaviour around eating

• Avoidance of activities requiring exposure of the body, such as swimming, or wearing excessively baggy or inappropriate clothing (e.g., lots of layers despite hot weather, to hide the body)

• Patterns or obsessive behaviours relating to body shape and weight (e.g., repeated weighing of self, excessive time spent body checking)

Body dysmorphic disorder

Body dysmorphic disorder is not an eating disorder. It is class ified as an “Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorder” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorder can co-occur.

Body dysmorphic disorder occurs when a person becomes preoccupied with one or more perceived defects or flaws in their physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others. People with body dysmorphic disorder often spend significant periods of time focusing on appearance concerns through behaviours such as mirror checking, excessive grooming and/or comparing appearance to others. This preoccupation causes significant distress and can impact on day-to-day life. Approximately 2% of people live with body dysmorphic disorder, with men and women a ffected relatively equally (15, 16).

See our page and fact sheet on Body Dysmorphic Disorder here.

Muscle dysmorphia is a form of body dysmorphic disorder which involves preoccupation with the idea that one’s body is too small or insufficiently lean or muscular. Muscle dysmorphia occurs almost exclusively in males (17).

It is never advised to ‘watch and wait’. If you or someone you know may be experiencing an eating disorder, accessing support and treatment is important. Early intervention is key to improved health and quality of life outcomes.

Recovery

It is possible to recover from an eating disorder, even if a person has been living with the illness for many years. The path to recovery can be long and challenging, however, with the right team and support, recovery is possible. Some people may find that recovery brings new understanding, insights and skills.

Treatment options

Access to evidence-based treatment has been shown to reduce the severity, duration and impact of an eating disorder. Treatment goals will depend on diagnosis, severity and duration of symptoms and the person’s values and preferences. Supporting the person to eat regular meals is a focus of treatment for many eating disorders. Addressing other emotional and psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, body image, and self-esteem are also important.

Health professionals providing support and treatment to males experiencing eating disorders may need to hold additional considerations in mind such as the importance of exploring and challenging ‘masculine’ concepts of strength, power and control for greater treatment engagement (18).

Most people can recover from an eating disorder with community-based treatment. In the community, the minimum treatment team includes a medical practitioner such as a GP and a mental health professional. Hospital-based treatment may be required when a person’s treatment needs include medical and/or psychiatric stabilisation, nutritional rehabilitation and/or more intensive treatment and support.

Getting help

If you think that you or someone you know may be experiencing an eating disorder, it is important to seek help immediately. The earlier you seek help the closer you are to recovery. Your GP is a good ‘first base’ to seek support and access eating disorder treatment.

To find help in your local area go to NEDC Support and Services.

Download the Eating Disorders in Males fact sheet here and infographic here.

References

1. Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S, Calzo JP, Brown TA, Mitchison D, Blashill AJ, Mond JM. The enigma of male eating disorders: A critical review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;57:1-11.

2. Deloitte Access Economics. Paying the price: the economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. Australia: Deloitte Access Economics; 2012.

3. Gordon AR., Moore LB, Guss C. Eating disorders among transgender and gender non-binary people. In: Nagata JM, Brown TA, Murray SB, Lavender JM, editors. Eating disorders in boys and men. Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021. p. 265-81.

4. Diemer EW, White Hughto JM, Gordon AR, Guss C, Austin SB, Reisner SL. Beyond the binary: differences in eating disorder prevalence by gender identity in a transgender sample. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):17-23.

5. Giordano S. Eating yourself away: Reflections on the ‘comorbidity’ of eating disorders and gender dysphoria. Clin Ethics. 2017;12(1):45-53.

6. Feder S, Isserlin L, Seale E, Hammond N, Norris ML. Exploring the association between eating disorders and gender dysphoria in youth. Eat Disord. 2017;25(4):310-7.

7. Mitchison D, Mond J. Epidemiology of eating disorders, eating disordered behaviour, and body image disturbance in males: a narrative review. J Eat Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

8. Hay P, Girosi F, Mond J. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian population. J Eat Disord. 2015;3(1):1-7.

9. Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, Hastings E, Edkins K, Lamont E, Nevins CM, Patterson RM, Murray HB, Bryant-Waugh R, Becker AE. Prevalence of DSM-5 avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric gastroenterology healthcare network. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(5):464-70.

10. Strother E, Lemberg R, Stanford SC, Turberville D. Eating disorders in men: underdiagnosed, undertreated, and misunderstood. Eat Disord. 2012;20(5):346-55.

11. Ali K, Farrer L, Fassnacht DB, Gulliver A, Bauer S, Griffiths KM. Perceived barriers and facilitators towards help-seeking for eating disorders: A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(1):9-21.

12. Griffiths S, Mond JM, Murray SB, Touyz S. Young peoples’ stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about anorexia nervosa and muscle dysmorphia. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(2):189-95.

13. Thapliyal P, Hay PJ. Treatment experiences of males with an eating disorder: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Transl Dev Psychiatry. 2014;2(1):25552.

14. Nagata JM, Ganson KT, Murray SB. Eating disorders in adolescent boys and young men: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(4):476-81.

15. Buhlmann U, Glaesmer H, Mewes R, Fama JM, Wilhelm S, Brähler E, Rief W. Updates on the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(1):171-5.

16. Veale D, Gledhill LJ, Christodoulou P, Hodsoll J. Body dysmorphic disorder in different settings: A systematic review and estimated weighted prevalence. Body Image. 2016;18:168-86.

17. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

18. Thapliyal P, Hay P, Conti J. Role of gender in the treatment experiences of people with an eating disorder: a metasynthesis. J Eat Disord. 2018;6(1):18.