Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

Prevalence of ARFID

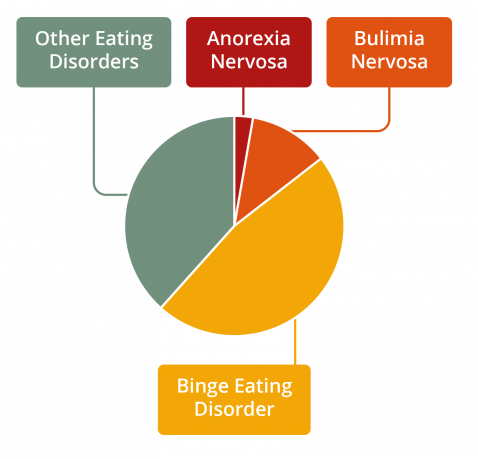

Any person, at any stage of their life, can experience an eating disorder. More than 1.1 million Australians are currently living with an eating disorder (1).

The 2024 Paying the Price report indicates that ARFID had a prevalence rate in 2023 of 0.13% (1). The prevalence is likely to be underestimated, with research on prevalence for ARFID being limited as it was

first included within the DSM-5 in 2013 (1).

ARFID is more commonly present in childhood and adolescence, however, it can occur in people of any age, gender, background, and sexual orientation (3). An Australian study reported a frequency of 0.3% among people aged 15 years and older (4).

Eating disorders are not a choice but are serious mental illnesses. Eating disorders can have significant impacts on all aspects of a person’s life – physical, emotional and social. The earlier an eating disorder is identified, and a person can access treatment, the greater the opportunity for recovery or improved quality of life.

Figure 1. Prevalence of eating disorders by diagnosis

What is ARFID?

A person with ARFID will avoid and restrict food, however this is NOT due to body image disturbance.

ARFID is a serious eating disorder characterised by avoidance and aversion to food and eating. The restriction is NOT due to a body image disturbance, but a result of anxiety or phobia of food and/or eating, a heightened sensitivity to sensory aspects of food such as texture, taste or smell, or a lack of interest in food/eating secondary to low appetite (2).

ARFID is more commonly present in childhood and adolescence, however, it can occur in people of any age, gender, background, and sexual orientation (3). ARFID is predicted to occur in 1 in 300 people in Australia (4).

ARFID is more than just ‘picky eating’. People with ARFID may avoid or only eat small amounts of food, or limit variety of foods leading to nutritional deficiencies. Distinguishing ARFID from fussy eating can be difficult, however adults and children with ARFID generally experience an extreme aversion to certain foods or have a general lack of interest in food or eating. A person’s avoidance of food becomes concerning when it affects their ability to meet their energy and nutritional needs, resulting in weight loss, malnutrition or an inability to maintain growth and development.

Characteristics of ARFID

Eating disturbance

A person with ARFID will avoid food and/or restrict their intake due to one or more of the following reasons:

• Restriction: The person shows little or no interest in food and/or eating

• Avoidance: The person avoids certain foods based on sensory characteristics (e.g. texture, smell, sight, taste)

• Aversion: The person has a fear or phobia of aversive consequences of eating (e.g. vomiting, choking, allergic reaction)

Complications

The restricted intake of food is associated with one or more of the following:

• Significant weight loss or, in children, a failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth. However, a person with ARFID can present at any weight.

• Significant nutritional deficiency due to limited food variety or insufficient intake of nutrients required for the body to function.

• Dependence on feeding via tube through the mouth, stomach or intestines (also known as enteral feeding) to meet nutritional needs.

• Marked interference with psychosocial functioning as the eating problem can have a significant impact on day-to-day life. Due to difficulties in eating with others, only eating particular foods, or taking much longer to eat, functioning at school, work, and home can be challenging.

How is ARFID different to other eating disorders?

ARFID may look similar to anorexia nervosa in that some people with ARFID will severely restrict their food intake, resulting in inadequate energy consumption and similar medical consequences. Other people with an ARFID diagnosis may eat enough to maintain body weight but due to limited variety of foods suffer consequences of specific nutrient deficiencies. In direct contrast to people with anorexia nervosa, people with ARFID do NOT avoid food or restrict their intake due to a fear of gaining weight or concern over their body, weight, and shape.

A diagnosis of ARFID will NOT be made if another eating disorder (e.g. anorexia nervosa) better explains the symptoms. Similarly, a health professional will make sure that the eating disturbance is not caused by another medical condition or best explained by another mental disorder, and the weight loss or failure to grow is NOT secondary to physical disorders such as gastrointestinal issues.

Is there a link between ARFID and autism?

ARFID can present on its own, or it can co-occur with other conditions too. The most common conditions that co-occur with ARFID are autism, ADHD and anxiety.

While there is some overlap between autism and ARFID (5), more research is needed to understand the relationship between the two. It is estimated that 21% of people with autism experience ARFID in their lifetime (7).

It is estimated that up to 26% of people diagnosed with ARFID will also have ADHD (8). More research is needed into the relationship between ADHD and ARFID.

Risk factors

The elements that contribute to the development of ARFID are complex, and involve a range of biological, psychological and sociocultural factors. Any person, at any stage of their life, is at risk of developing an eating disorder. An eating disorder is a mental illness, not a choice that someone has made.

Warning signs

Physical

• Delayed growth

• Weight loss

• In children, a failure to gain weight

• Reduced appetite

• Brittle nails, dry hair, hair loss

• Tiredness or lack of energy

• Other symptoms of micronutrient deficiencies

Psychological

• Anxiety and/or distress around food and mealtimes

• Difficulty concentrating or learning

Behavioural

• Lack of interest in food and/or eating

• Refusal to eat or a reduction in foods previously eaten

• Slow eating

• Stating a fear of choking or eating certain foods

• Fear of vomiting of certain foods

• Difficulty eating meals with others

• Only eating a small number of foods. These foods may be similar in taste, texture, smell, or sight

It is never advised to ‘watch and wait’. If you or someone you know may be experiencing an eating disorder, accessing support and treatment is important. Early intervention is key to improved health and quality of life outcomes.

Impacts and complications

A person with ARFID may experience serious medical and psychological consequences.

Medical

The restriction of food can result in a lack of essential nutrients and calories that the body needs to function normally. This could result in serious medical complications including:

• Heart problems

• Osteoporosis: a reduction in bone density caused by a specific nutritional deficiency

• Nutritional deficiencies including anaemia or iron deficiency, low vitamin A, low vitamin C

• Malnutrition characterised by fatigue, weakness, brittle nails, dry hair, hair loss, and difficulty concentrating, low energy

• Growth failure, failure to thrive, or stunted growth in children and adolescents

• Kidney and liver failure

• Electrolyte disturbances

• Low blood sugar

• Gastrointestinal problems

Psychological

Some of the psychological impacts and complications associated with ARFID include:

• Anxiety

• Depression

• Social anxiety or social withdrawal

• Low self-esteem

Treatment options

ARFID is a relatively new diagnosis and the research is still growing around which treatments are effective. For all eating disorders, early intervention and treatment are likely to lead to better outcomes. The goals of treatment for ARFID will be determined by the underlying cause for the avoidance of food, for example, a phobia, an aversion to texture, or a lack of interest in food.

Current evidence suggests cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for people with ARFID (2). Treatment may involve gradually exposing the person to feared foods, relaxation training, and support to change eating behaviours.

Responsive feeding therapy (RFT) has also been used for the treatment of ARFID in children, however the guiding principles of RFT could also be applied for adolescents and adults (6). Responsive feeding involves parents or carers establishing mealtime routines with pleasant interactions and few distractions, modelling mealtime behaviour, and allowing the child to respond to hunger cues (6).

There are no medications for treating ARFID (2). If someone with ARFID also experiences anxiety or depression, there are some medications that can help with these symptoms. Your GP will help you to decide on the best treatment for you.

Some people with ARFID will need admission to hospital if the restriction causes severe medical complications, such as cardiac or gastrointestinal problems, or blood pressure or heart rate fluctuations. Treatment in hospital can ensure the person receives the nutritional intake they need for their body to function normally.

Most people can recover from an eating disorder with community-based treatment. In the community, the minimum treatment team includes a medical practitioner such as a GP and a mental health professional.

Recovery

It is possible to recover from ARFID, even if a person has been living with the illness for many years. The path to recovery can be long and challenging, however, with the right team and support, recovery is possible. Some people may find that recovery brings new understanding, insights and skills.

Getting help

If you think that you or someone you know may have ARFID, it is important to seek help immediately. The earlier you seek help the closer you are to recovery. Your GP is a good ‘first base’ to seek support and access eating disorder treatment.

To find help in your local area go to NEDC Support and Services. This webpage includes information on finding Credentialed mental health professionals and dietitians trained in eating disorders. f you would like to discuss your concerns with a counsellor, we recommend contacting the National Butterfly Helpline.

Download the ARFID fact sheet here.

References

1. Butterfly Foundation. Paying the Price, Second Edition. The economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia: Deloitte Access Economics; 2024.

2. Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a three-dimensional model of neurobiology with implications for etiology and treatment. Current psychiatry reports. 2017;19(8):1-9.

3. Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating disorders: current perspectives on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2016;12:213.

4. Hay P, Mitchison D, Collado AEL, González-Chica DA, Stocks N, Touyz S. Burden and health-related quality of life of eating disorders, including Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in the Australian population. Journal of eating disorders. 2017;5(1):1-10.

5. Dovey TM, Kumari V, Blissett J. Eating behaviour, behavioural problems and sensory profiles of children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), autistic spectrum disorders or picky eating: Same or different? European Psychiatry. 2019;61:56-62.

6. Wong G, Rowel K. Understanding ARFID Part II: Responsive Feeding and Treatment Approaches National Eating Disorder Information Centre - Bulletin. 2018;33(4).

7. Koomar T, Thomas TR, Pottschmidt NR, Lutter M, Michaelson JJ. Estimating the Prevalence and Genetic Risk Mechanisms of ARFID in a Large Autism Cohort. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Jun 9;12:668297.

8. Kambanis PE, Kuhnle MC, Wons OB, Jo JH, Keshishian AC, Hauser K, Becker KR, Franko DL, Misra M, Micali N, Lawson EA, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidities in children and adolescents with full and subthreshold avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2020 Feb;53(2):256-265.