Other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED)

Any person, at any stage of their life, can experience an eating disorder. More than one million Australians are currently living with an eating disorder (1).

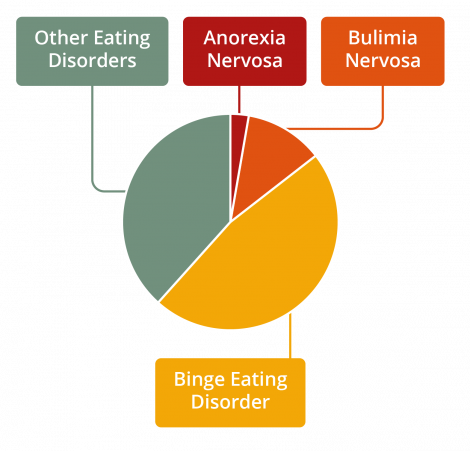

Of people with eating disorders, 3% have anorexia nervosa, 12% bulimia nervosa, 47% binge eating disorder and 38% with other eating disorders (1).

Eating disorders are not a choice but are serious mental illnesses. Eating disorders can have significant impacts on all aspects of a person’s life – physical, emotional and social. The earlier an eating disorder is identified, and a person can access treatment, the greater the opportunity for recovery or

improved quality of life.

Figure 1. Prevalence of eating disorders by diagnosis

What is OSFED?

A person with OSFED does not meet the criteria to be diagnosed with another eating disorder, however, is presenting with many of the symptoms of other eating disorders. OSFED is just as serious as other eating disorders and is associated with complex medical and psychiatric complications.

A person with OSFED may present with many of the symptoms of other eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder but will not meet the full criteria for diagnosis of these disorders. This does not mean that the eating disorder is any less serious or dangerous.

OSFED is a serious, complex and potentially life-threating mental illness that occurs in adults, adolescents and children. The medical complications and eating disorder thoughts and behaviours related to OSFED are as severe as other eating disorders.

Characteristics of OSFED

People with OSFED commonly present with disturbed eating habits, and/or a distorted body image and/or overvaluation of shape and weight and/or an intense fear of gaining weight. OSFED is the most common eating disorder diagnosed for adults as well as adolescents (2, 3) and affects all genders.

The diagnosis of OSFED might be further specified using the following terms:

- Atypical anorexia nervosa: All of the criteria are met for anorexia nervosa except that despite significant weight loss, the individual’s weight is within or above the normal range. A person with atypical anorexia nervosa can experience many of the same physiological complications as someone with anorexia nervosa.

- Bulimia nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration: All of the criteria for bulimia nervosa are met, except that binge eating and compensatory behaviours occur, on average, less than once a week and/or for less than three months.

- Binge eating disorder of low frequency and/or limited duration: All of the criteria for binge eating disorder are met, except that the binge eating occurs, on average, less than once a week and/or for less than three months.

- Purging disorder: Recurrent purging behaviour to influence weight or shape (e.g., self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications) in the absence of binge eating.

- Night eating syndrome: Recurrent episodes of night eating as manifested by eating after awakening from sleep or by excessive food consumption after the evening meal. There is awareness and recall of the eating and the eating causes significant distress to the individual.

While the goal of diagnosis is to accurately describe symptoms and seek the right help for them, some people have other significant eating and feeding issues and distorted body image which are not covered by these categories. Early intervention in any eating or body image disturbance can prevent the worsening of symptoms and risk of developing an eating disorder.

Risk factors

The factors that contribute to the development of OSFED will differ from person to person and involve biological, psychological and sociocultural factors. Any person, at any stage of their life, is at risk of developing an eating disorder. An eating disorder is a mental illness, not a choice that someone has made.

Warning signs

The warning signs of OSFED can be physical, psychological, and behavioural. It is possible for someone with OSFED to display a combination of these symptoms, or no obvious symptoms.

Physical

• Sudden weight loss, gain or fluctuation

• Inability to maintain normal body weight for age and height, failure to grow as expected

• Loss or disturbance of menstruation

• Fainting or dizziness

• Sensitivity to the cold

• Bloating, constipation, or the development of food intolerances

• Fatigue or lethargy

• Compromised immune system (e.g., getting sick more often)

• Signs of vomiting such as swollen cheeks or jawline, calluses on knuckles, or damaged teeth

Psychological

• Preoccupation with eating, food, body shape, or weight

• Body dissatisfaction or negative body image

• Heightened anxiety or irritability around mealtimes

• Heightened sensitivity to comments or criticism (real or perceived) about body shape or weight, eating, or exercise habits

• Low self-esteem and feelings of shame, self-loathing or guilt

• Body dissatisfaction or negative body image

• Depression, anxiety, self-harm, or suicidality

• ‘Black and white’ thinking - rigid thoughts about food being ‘good’ or ‘bad’

Behavioural

• Repetitive dieting behaviour such as counting calories, skipping meals, fasting, or avoidance of certain foods or food groups

• Evidence of binge eating such as disappearance or hoarding of food

• Evidence of vomiting or misuse of laxatives, appetite suppressants, enemas and/or diuretics

• Frequent trips to the bathroom during or shortly after meals

• Compulsive or excessive exercising

• Eating at unusual times and/or after going to sleep at night

• Patterns or obsessive rituals around food, food preparation, and eating

• Changes in food preferences

• Patterns or obsessive behaviours relating to body shape and weight

• Social withdrawal or isolation from friends and family

• Secretive behaviour around eating

It is never advised to ‘watch and wait’. If you or someone you know may be experiencing an eating disorder, accessing support and treatment is important. Early intervention is key to improved health and quality of life outcomes.

Impacts and complications

The risks associated with OSFED are severe. People with OSFED will experience risks similar to those of the eating disorder their behaviours most closely resembles.

Medical

Some of the medical impacts and complications associated with OSFED include:

• Chronic sore throat, indigestion, heartburn and reflux

• Inflammation and rupture of the oesophagus and stomach from frequent vomiting

• Gastrointestinal problems such as chronic constipation or diarrhoea

• Impairment of kidney, liver, or pancreatic function

• Electrolyte disturbance, including potassium and sodium

• Osteoporosis or osteopenia: a reduction in bone density caused by a specific nutritional deficiency

• Heart problems such as irregular or slow heartbeat which can lead to an increased risk of heart failure

• Blood pressure disturbance (either high or low)

• Loss of or disturbance to menstruation

• Increased risk of infertility

• Gastrointestinal problems

Psychological

Some of the psychological impacts and complications associated with OSFED include:

• Extreme body dissatisfaction/distorted body image

• Obsessive thoughts and preoccupation with eating, food, body shape and weight

• Social withdrawal

• Feelings of shame, guilt, and self-loathing

• Depressive or anxious symptoms and behaviours

• Self-harm or suicidality

• Substance misuse

Recovery

It is possible to recover from OSFED, even if a person has been living with the illness for many years. The path to recovery can be long and challenging,

however, with the right team and support, recovery is possible. Some people may find that recovery brings new understanding, insights and skills.

Treatment options

The goals of treatment for OSFED will be determined by the subtype diagnosis, for example bulimia nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration (4). Supporting the person to eat regular meals is a focus of treatment for many eating disorders and addressing other emotional and psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, body image, and self-esteem are also important.

Research suggests psychological therapies are effective in treating OSFED. The specific therapy chosen will be determined by the eating disorder that the eating problem most closely resembles.

These include:

- Family Based Treatment (FBT) for atypical anorexia in children and adolescents

- Maudsley anorexia nervosa treatment (MANTRA) for atypical anorexia in adults

- Specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM) for atypical anorexia in adults

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Enhanced (CBT-E) for atypical anorexia in adults

- Eating disorder-focused focal psychodynamic therapy for atypical anorexia in adults

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Enhanced (CBT-E) for atypical anorexia, bulimia nervosa/binge eating disorder low frequency in children, adolescents, and adults

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Guided Self Help (CBT-GSH) for bulimia nervosa/binge eating disorder low frequency in adults (adapted from (5))

Most people can recover from an eating disorder with community-based treatment. In the community, the minimum treatment team includes a medical practitioner such as a GP and a mental health professional.

Inpatient treatment may be required when a person needs medical and/or psychiatric stabilisation, nutritional rehabilitation and/or more intensive treatment and support.

Getting help

If you suspect that you or someone you know has OSFED, it is important to seek help immediately. The earlier you seek help the closer you are to recovery. Your GP is a good ‘first base’ to seek support and access eating disorder treatment. To find help in your local area go to NEDC Support and Services.

Download the OSFED fact sheet here.

References

1. Deloitte Access Economics. Paying the price: the economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. Australia: Deloitte Access Economics; 2012.

2. Santomauro DF, Melen S, Mitchison D, Vos T, Whiteford H, Ferrari AJ. The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):320-8.

3. Mitchison D, Mond J, Bussey K, Griffiths S, Trompeter N, Lonergan A, et al. DSM-5 full syndrome, other specified, and unspecified eating disorders in Australian adolescents: prevalence and clinical significance. Psychol Med. 2020;50(6):981-90.

4. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. National clinical practice guideline number CG9. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2004.

5. Heruc G, Hurst K, Casey A, Fleming K, Freeman J, Fursland A, et al. ANZAED eating disorder treatment principles and general clinical practice and training standards. J Eat Disord. 2020;8(1):63.