Identification refers to the detection of warning signs or symptoms, and engagement with the person who may be experiencing an eating disorder, to support access to an initial response. In some instances, warning signs or symptoms may be self-identified, and the person may seek out an initial response themselves.

Community members and professionals with a role in identification include (but are not limited to) families/supports, general practitioners (GPs), teachers, school counsellors and nurses, nurse practitioners, dietitians, mental health professionals, dentists, sports and fitness professionals, physical therapists, and medical specialists. Digital tools and resources can also support identification for people experiencing an eating disorder and families/supports. Identifying warnings signs or symptoms early in the eating disorder (or sub-threshold eating disorder) can help to shorten the duration of untreated illness (the time between first onset of a diagnosable illness and receiving evidence-based treatment).

Shorter duration of untreated illness is associated with better treatment outcomes for eating disorders (1), reducing the impact of the eating disorder on the person and their family/supports and community. Many people experiencing or at risk of an eating disorder are not identified early in the course of illness (or sub-threshold illness) (2, 3, 4). People frequently present to primary health care settings for other concerns (3, 5), but the eating disorder is not identified, and evidence-based treatment is not accessed or provided. A lack of awareness of different types of eating disorder presentations (such as binge-eating disorder and OSFED) impacts on identification (2) and this can be exacerbated by weight stigma and weight-centric approaches, resulting in eating disorders being missed or discounted.

You can read more about early intervention here. For health professionals, learn more about identification including screening and assessment tools here.

We encourage you to read the Identification section in the National Strategy for further information about areas of focus in identification, as well as standards and actions for building this element of the system of care. Please see pages 41-44.

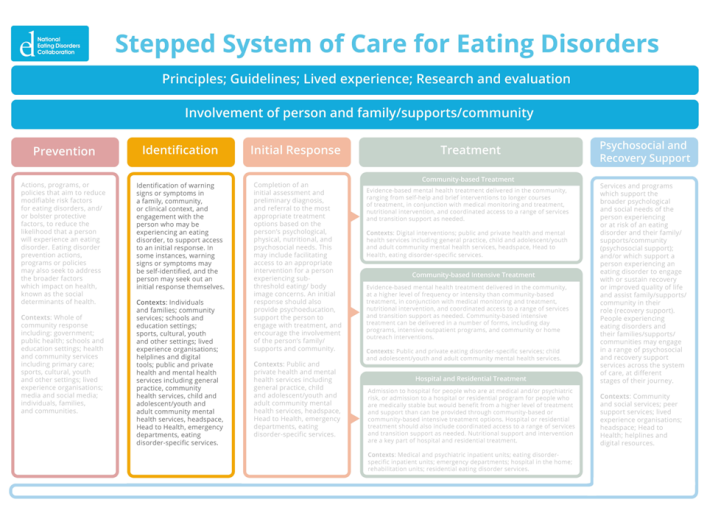

Click to read more about the Stepped System of Care.

References

1. Andrés-Pepiñá S, Plana MT, Flamarique I, Romero S, Borràs R, Julià L, et al. Long-term outcome and psychiatric comorbidity of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020 Jan;25(1):33-44.

2. Hamilton A, Mitchison D, Basten C, Byrne S, Goldstein M, Hay P, et al. Understanding treatment delay: Perceived barriers preventing treatment-seeking for eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 12;56(3):248-59.

3. Ivancic L, Maguire S, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Harrison C, Nassar N. Prevalence and management of people with eating disorders presenting to primary care: A national study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021 Nov;55(11):1089-100.

4. Striegel Weissman R, Rosselli F. Reducing the burden of suffering from eating disorders: Unmet treatment needs, cost of illness, and the quest for cost-effectiveness. Behav Res Ther. 2017 Jan;88:49-64.

5. Fursland A, Watson HJ. Eating disorders: A hidden phenomenon in outpatient mental health? Int J Eat Disord. 2014 May;47(4):422-5.