Issue 69 | The impact of COVID-19 on Eating Disorders

Contents:

Q&A with Associate Professor Sloane Madden

Q&A with clinical psychologist Mandy Goldstein with FBT and CBTe case descriptions

Video interview with EDQ general manager Belinda Chelius

Editor's Note:

The mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been acknowledged by the Australian government as a cause for great concern, and this encompasses the eating disorder sector. Quarantine, lockdown and isolation have interfered with treatment and recovery, increased the presence of symptoms and instances of relapse and delayed or stopped important research. Demands on clinicians, hospitals, carers and supports have risen markedly. There have also been ‘silver linings”, such as greater flexibility regarding appointments, adaptation to telehealth and the use of social media to create supportive communities.

A report compiled by NEDC from information gathered from twenty-five ED-specific services in WA, SA, NSW, VIC and QLD found:

- The COVID 19 pandemic has generated a marked increase in presentations of both new and relapsing eating disorders, and in the level of acuity and severity of these presentations.

- Increased demand for community and in-patient services, along with an increase in complexity of presentations including high psychiatric and medical risk, has impacted on supports available at each level of the system of care.

In this issue, we interview Associate Professor Sloane Madden, this year’s co-winner of the ANZAED Lifetime Achievement Award with Chris Thornton. A/Prof. Madden explains the critical importance of evidence-based care in medical treatment and how COVID-19 has added complexity to multi-disciplinary treatment.

Clinical psychologist and ANZAED Secretary Mandy Goldstein adds her perspective as a practitioner, noting that due to COVID-19 greater flexibility is required in learning new technical skills. She provides case descriptions to adapting FBT and CBTe for a virtual era.

Eating Disorders Queensland (EDQ) general manager Belinda Chelius talks about the organisational difficulties involved in maintaining connection and community during the COVID-19 lockdown, which she says created the “perfect storm” for eating disorders.

In this e-Bulletin we also mark NAIDOC Week, delayed by several months this year due to COVID-19, with a report from NEDC Primary Health Project Manager Louise Dougherty.

The pool of knowledge forming the evidence base in the research field is growing every day. Recent journal articles focusing on the ramifications of COVID-19 on the eating disorder field include a study to evaluate the impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on patients, considering the role of pre‐existing vulnerabilities; respondents reporting the return of the ED voice; an increase in practical demands placed on carers due to a reduction in professional support; a comparative study which could inform the development of new preventative measures; and a survey of researchers in the eating disorders field which found women expressing concerns about their future career due to the pandemic. See links below, and go to our our COVID-19 page for resources and further reading.

Further reading links:

Castellini, G., Cassioli, E., Rossi, E., Innocenti, M., Gironi, V., Sanfilippo, G., Felciai, F., Monteleone, A. M., & Ricca, V. (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 epidemic on eating disorders: A longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(11), 1855-1862. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23368

Weissman, R. S., Klump, K. L., & Rose, J. (2020). Conducting eating disorders research in the time of COVID‐19: A survey of researchers in the field. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(7), 1171-1181. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23303

McCombie, C., Austin, A., Dalton, B., Lawrence, V., & Schmidt, U. (2020). “Now It's Just Old Habits and Misery”–Understanding the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on people with current or life-time eating disorders: a qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 589225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.58922

Clark Bryan, D., Macdonald, P., Ambwani, S., Cardi, V., Rowlands, K., Willmott, D., & Treasure, J. (2020). Exploring the ways in which COVID‐19 and lockdown has affected the lives of adult patients with anorexia nervosa and their carers. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(6), 826-835. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2762

Papandreou, C., Arija, V., Aretouli, E., Tsilidis, K. K., & Bulló, M. (2020). Comparing eating behaviours, and symptoms of depression and anxiety between Spain and Greece during the COVID‐19 outbreak: Cross‐sectional analysis of two different confinement strategies. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(6), 836-846. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2772

Haripersad, Y. V., Kannegiesser-Bailey, M., Morton, K., Skeldon, S., Shipton, N., Edwards, K., Newton, R., Newell, A., Stevenson, G., & Martin, A. C. (2020). Outbreak of anorexia nervosa admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 0(1). http://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-319868

Jones, P. D., Gentin, A., Clarke, J., & Arakkakunnel, J. (2020). Eating disorders double and acute respiratory infections tumble in hospitalised children during the 2020 COVID shutdown on the Gold Coast. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15248

Q&A with Sloane Madden

Associate Professor Sloane Madden, the co-winner of this year’s ANZAED Lifetime Achievement Award, reflects on his 20-year career and shares his insights on the biggest issues affecting the ED sector.

How did you come to work in eating disorders?

I first started working with eating disorders as a child psychiatry registrar at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead just over 20 years ago. At that time, the service while providing excellent care was very small and lacked a clear focus moving forward. Being new to the hospital gave me the opportunity, in partnership with my adolescent medicine colleague Michael Kohn, to set up an effective eating disorder program with a strong research focus. After that the service grew until it took over all of my clinical and research focus.

What have been the most rewarding aspects of your work?

This job has given me enormous opportunities and satisfaction over the past 20 years. I work with a fantastic team full of hard-working and talented people and it has been a real privilege to be part of such a team. It is incredibly satisfying to work with young people and their families to be able to assist them through this difficult time in their lives and allow them to fulfil their potential. It is always great to hear from these young people later in life and hear about the successes and achievements. Finally, it has been really satisfying to have been involved in research which has helped to guide and shape treatment for young people with eating disorders.

How important is being evidence-based and evidence-generating to enlarging knowledge?

Evidence-based care is a cornerstone of medical treatment and critical to providing optimum patient care, and the treatment of people with eating disorders is no different. Outcomes in eating disorders, even with early recognition and the application of current evidence-based treatment, are still less than ideal. For that reason it is critical that not only do we follow the evidence available but, in cases where that evidence does not exist, that we monitor and review the care we provide to generate evidence to allow better outcomes for not only those people in our care but for all people with eating disorders.

In your experience, how has COVID-19 impacted the lives of people with eating disorders and the professionals who work with them? What are the complications due to the pandemic?

The effects of COVID-19 have been significant on many of the young people that I have seen. Our service has seen a 40% increase in admissions for acute medical complications of eating disorders. For many young people COVID-19 took away key supports including peers, school, sport, dance and music as well as placing pressure on their families and normal support structures. For many young people these changes were key in the onset of their eating disorders. Treatment became harder to access while, for many, remote therapy was less helpful. In our service we have continued to see people face to face but we do so while wearing surgical masks, being socially distanced and with many of our treatment services severely limited. It has also been much harder to refer young people on to outpatient care, placing significant pressures on the team I work with to meet current clinical demands.

How important is the multidisciplinary team in treating child and adolescent eating disorders? Has the functioning of the multidisciplinary team been affected by COVID-19?

Multidisciplinary care has always been the basis of our treatment of eating disorders. Unfortunately, due to COVID-19, meetings are done remotely and multidisciplinary ward rounds have been severely limited. The lack of face-to-face communication has added complexity to multidisciplinary care and taken away some of the satisfaction of working in this model.

What do you consider to be the greatest issues affecting the eating disorders sector in the current climate? What can we learn from this for the national context?

Key issues remain a significant lack of services and resources to meet the current demand for timely evidence-based care, putting enormous pressure on those with eating disorders and their carers trying to access care, and also on existing teams unable to meet demand and provide safe and effective care for all of those who need it. There is a need to dramatically improve resources to address this need. I am not sure such a lack of even basic care would be tolerated in any other area of health care.

What do you think of the wider use of telehealth in treatment?

Our service has used telehealth over the past twenty years and while it allows greater flexibility in providing treatment it will never replace the need for face-to-face care. We have many rural and remote families who prefer to drive often for many hundreds of kilometres over many hours to access in-person treatment. Where telehealth care is used it works best when it is done in conjunction with local services who can see the patient remotely [face to face where they live]. Anecdotally many patients have expressed their dissatisfaction with telehealth care and preference for at least some of their care to be provided face to face.

With the benefit of your experience, what directions do you see emerging in the future of eating disorders research?

I think there will be a greater focus on genetics to allow for earlier diagnosis and more personalised care. In addition, I think we will be looking at novel treatments including neurostimulation to enhance outcomes of current psychological interventions in care.

Associate Professor Sloane Madden is recognised for his expertise in the management of and research in the field of child and adolescent eating disorders (ED). He is the Eating Disorder Service co-ordinator for the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network. He has consulted broadly on the development of child and adolescent eating disorder services in NSW, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, New Zealand and Singapore and been extensively involved in policy and guideline development on a state and national level. He is the medical director of the Eating Disorder Program at Northside Clinic (St Leonards).

Sloane is a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) and of the Academy of Eating Disorders (USA) where he served as the board member responsible for research practice integration. He is past-president of the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Eating Disorders (ANZAED). He is an active researcher in the field of child and adolescent eating disorders.

Q&A with Mandy Goldstein

Clinical psychologist Mandy Goldstein highlights the challenges and benefits of translating research into practice in the time of COVID-19, and dealing with issues ranging from pets disrupting sessions to managing walk-outs and weigh-ins online.

Quick Links: Case descriptions for FBT and CBTe.

Tell us about your work with eating disorders.

I have worked in the field since 2007, though while training, I had little idea I was interested in eating disorders (EDs). It started with my first external placement supervisor inviting me to be a co-therapist on a day program group for teens with EDs, ostensibly to get my hours up, while filling a staffing gap, as interns do. But the distress of those intelligent, interesting and tortured young women drew me in, and here I am close to 15 years later.

Since that unexpected start, my passion for EDs has grown into a genuine commitment to changing the conversation around the thin ideal and weight stigma; ensuring treatment focuses on what is core to EDs and their treatment; and helping people move towards accepting the bodies they have, and a fuller sense of themselves as a person of value outside of weight and shape.

How has COVID-19 impacted or changed the services you provide?

There was the practical impact at the start of COVID-19 to “pivot” the practice almost overnight into a virtual version of itself. I know I was not alone in scrambling for sustainable, affordable and secure telehealth platforms, digital knowledge, and new methods of communication with clients. We all needed to find a confidential workspace at home and become literate in a digital world of end-to-end encryption and other compliance requirements I suspect few of us had previously stopped to consider.

This led to the development of new micro-skills, for example: learning how to manage technology glitches; track a distressed client via screen; or to extend empathy without being able to hand over the tissues.

From a service perspective, we continued to provide evidence-based treatment throughout the pandemic. But the way in which we offered those services certainly shifted. Prior to COVID-19 most clinicians are likely to have strongly discouraged treatment via telehealth, supporting in-person attendance. Many would have hesitated to undertake elements of certain treatments in an online modality, without the containment of an in-person relationship. In working via telehealth, clinicians have been required to develop more flexibility in the treatment we are willing to undertake virtually.

There have been obvious changes to the way we carry out evidence-based treatment. For example, rethinking how to manage weigh-ins and family meals in family-based treatment (FBT), and mirror exposure or social eating challenges in Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBTe). However, reflecting on why we incorporate certain elements or how to alter treatment for a virtual modality, has helped develop a clearer rationale for those aspects which are core to good ED treatment. Two helpful "how to" resources were published at the early stages of COVID-19 specifying ways to alter both CBTe (Waller et al., 2020) and FBT (Matheson et al., 2020). For clinicians interested, I have provided two brief case descriptions, for FBT and CBTe. While a single case is unable to detail every possible alteration, each provides a description of some of the core components of CBTe and FBT treatment and how the protocols were altered or used more flexibly to accommodate working via telehealth.

You co-presented a Research-Practice Global Think Tank on Eating Disorders in the time of COVID at the virtual ICED Conference. How important is the rapidly expanding body of research into eating disorders during COVID-19?

One of the most important contributions research made early on was in helping clinicians develop confidence to take up telehealth. In summarising existing telehealth practice and ethical guidelines, researchers established the feasibility, validity, satisfaction and cost effectiveness of psychiatry via telehealth. (Sansom-Daly et al., 2016; and Smith et al., 2020.) A gem I discovered at the start of the pandemic was a systematic review which showed that while clinicians rated therapeutic alliance lower for telehealth than in-person treatment, clients rated it as at least equivalent (Simpson and Reid, 2014). That helped me understand much anxiety about shifting to a virtual treatment modality lay with the clinician, not the patient, and to have confidence that working virtually was unlikely to disadvantage clients.

The development of an ED-specific evidence base has helped challenge unhelpful assumptions, and supported clinicians to ensure focused treatment for their clients. For example, early fears about gaining the “quarantine 15” were widespread. However, they have been shown to be unfounded among college students in a study by Keel and colleagues (2020).

Intolerance of uncertainty has emerged as another risk factor for increased anxiety, and this in turn, for risk of ED onset or exacerbation. However, Baenas et al. (2020) identified a lack of self-directedness, defined as an ability to regulate behavior towards identified goals, as specifically contributing to poor adjustment to confinement in the pandemic, and increased likelihood of ED deterioration. Having this information means we are able to bring a concept like self-directedness into focus in treatment and help clients develop this part of themselves, if relevant.

Similarly, there has been research showing an increase in compulsive exercise risk for people with EDs through lockdown (Phillipou et al. 2020). However, another study linked exercise risk to trait intolerance of uncertainty, showing that exercise was not likely to increase if intolerance of uncertainty was related to COVID-19 alone, rather than a character trait (Scharmer et al, 2020). So, the expanding body of research has really supported clinicians in targeting interventions more specifically depending on the individual we are working with.

In the ICED think tank, Brittany Matheson from Stanford University spoke about adapting FBT to telehealth. She cited issues including monitoring weighing, dealing with interruptions and exits and building rapport. With your experience in FBT, have you experienced challenges and opportunities in delivering this treatment during COVID-19?

Certainly, both. The opportunities include that for families who had previously found it challenging to attend sessions, telehealth has made this easier. With more people working from home, working parents have been present to provide meal supervision. My experience was that weight restoration was typically well managed during lockdown because it was easier to provide the necessary level of support.

Among the challenges, it is harder to develop the same level of engagement and containment with families in their own homes. I have had families call from a car, pets disrupt sessions, or family members seeing it as normal to have a snack or make tea in the middle of a session. One of the active ingredients of FBT is that the newness of the environment of therapy and the crisis of the ED are thought to stimulate parents to take action. It has been harder to instil this momentum when families remain in their own environments, and don’t have that challenge to their everyday patterns, or what FBT would call homeostasis.

In terms of the clinical application of FBT, doing a family meal virtually means the clinician has less opportunity to use proximity to create intensity. When I do a family meal in the room, I might get people to sit in different places and sit really close to the young person, which provides additional support but also an element of intensity, to encourage eating. It can be harder to make those physical changes when managing different dynamics through the screen.

Decisions about who does the weigh-in have been challenging, and in my opinion have yielded mixed outcomes. I have families where parents have taken charge of weigh-ins without a hitch; and those where doing so has intensified relational tensions and added strain. Encouraging patients to attend a GP for weigh-ins has been met with resistance, as patients are reluctant to pay for a consult to achieve something they can do at home. This has had to be negotiated on a case-by-case basis.

The walk-out example is an interesting one, and one that I’ve found is no different from the walk-outs in the office. It is not unusual for a young person to leave the office at times if highly distressed, and the way we would typically manage that is to invite the parents to follow the young person, ensure their safety and work as a team to get them back in the room. Similarly with online walk-outs through turning off a device or leaving the room, we have dealt with this by getting the parents back on the call, and discussing how they would like to manage their young person’s distress and safety, with a view to getting them back on the call if possible.

What further difficulties are there for teenagers and what approaches have you found valuable? Is it easier for teens to disconnect from treatment during COVID-19?

I have found adolescents’ response to online work really mixed. For most, talking through their concerns, or taking more time to get to know the young person has been helpful. But for a small percentage, nothing has shifted their belief they are unable to trust someone they have not met in person. However, I have not seen this lead to disconnection from treatment, as the responsibility for attending sessions mostly lies with parents.

For teens the biggest issue in working through lockdown was the impact of social disconnection and isolation, and there was a lot of complaint about spending too much time with their families. Developmentally, that’s absolutely normal, and it has been genuinely tough on teens to be at more of a distance from peers, and also to have missed out on their usual creative or sporting outlets, or milestones like ‘schoolies week’ or formals. My sense is for many, there has been a marked uncertainty about the future, and I have seen a lot more hopelessness in the teens I am working with.

How can technology be used to improve access to care?

The digital space has really exploded around this, but even before COVID-19 there were online apps such as Recovery Record, offering opportunities for patients to monitor or log their eating, thoughts and feelings online. I get much better adherence from people using an app on their smart phone, than carrying around a notebook and pen. There are new apps being researched all the time, all with a view to improving flexible access to care, as well as affordability of treatment.

What do you think might be the long-term impacts of COVID-19 for people with eating disorders and the professionals who work with them?

For clinicians, the most striking long-term impact is likely increased treatment demand. The practice has never been busier, literally taking the number of referrals in a day that we might have seen in a fortnight. Wait-lists are lengthy, and patients and families are finding it very difficult to access treatment. The pandemic has really thrown a spotlight on a substantial workforce deficiency, which I suspect is contributing to clinician burn-out. Long-term, my hope is we are encouraged as clinicians to improve our self-care and enhance our capacity to manage caseloads and session scheduling more thoughtfully; as well as to train more clinicians in the field.

I have also seen the pandemic as an opportunity for real innovation and collaboration. Glenn Waller and colleagues around the world developed a shared document very early in the pandemic, which was widely circulated and edited by specialists in the field, to provide clinicians with viable ways of altering CBTe for virtual use. This kind of collaboration and flexibility is exciting and necessary.

For clients, I am hopeful there might be some positive long-term impacts such as increased access under Medicare to more flexibly delivered treatment, especially for those living remotely. However, for those with EDs, behaviours like social withdrawal or isolation have become marked, and have contributed to an increased challenge in re-engaging with the world following periods of lockdown. For many, there has been a lot more anxiety, and intolerance of uncertainty, both of which are known psychosocial stressors likely to trigger or exacerbate disordered eating. My sense is long beyond a vaccine, there might be those who continue to struggle with increased anxiety and uncertainty.

This also presents a long-term opportunity, in that the pandemic has highlighted a need to reconsider the way we look at and manage uncertainty, for clients and clinicians alike. I see this less as a clinical or exclusively client concern, and more as an aspect of what it is to be human and living through such a challenging experience together.

Dr Mandy Goldstein is a clinical psychologist with more than 12 years’ experience in the treatment of EDs and trauma. She is the Principal Clinical Psychologist at Mandy Goldstein Psychology, and works as an Associate at the Redleaf Practice, both in Sydney, focusing on the treatment of EDs. Mandy has been providing family-based treatment (FBT) for adolescents with eating disorders in a private practice setting since 2008 and provides consultation and supervision to trainee psychologists in FBT, as well as the treatment of EDs across the age range and trauma more generally.

Her research has been published in international peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences. She is an Adjunct Fellow in the Department of Psychology at Macquarie University and is Secretary of the Australia and New Zealand Academy for Eating Disorders (ANZAED).

Video interview with Belinda Chelius

See the video here.

Senior social work clinician Belinda Chelius has had a long association with Eating Disorders Queensland (EDQ). EDQ provides integrated eating disorder support services to individuals and families living with and recovering from an eating disorder, their carers and loved ones. Belinda had no hesitation in “snapping up” the role of general manager three and a half years ago. She describes it as a very good fit given her social justice background and interest in creating a community based on connection, equity and mentoring – which has been tested by the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I’ve got a Masters in social work so I’ve been a clinical practitioner myself for many many years, working in complex mental health and then eating disorders, personality disorders … on the severe and enduring scale,” she said. “I’ve also got a very strong social justice, feminist, practice framework and lens that I look at the world through and EDQ is a very good fit for me in that sense.”

EDQ MODEL

EDQ takes a unique approach, working alongside multidisciplinary teams supporting clients – including psychiatrists, dietitians, GPs and hospital staff – but with a primary focus on addressing broader social constructs such as the importance of a person’s environment.

“We’ve always been that organisation that sat alongside a very purist medical model. We very much advocate that there (is a) different model and different way of looking at EDs through that lens of social constructs, and how we view eating disorders as not just an individual pathology but rather how it looks in the environment (such as the impact of trauma) and the conversation we have around particularly women’s bodies and the expectation of how women should look and act,” she said.

“We know that that shifted a lot to the marginalised groups like our LGBTIQ, our Indigenous groups, our African-American population and of course men have come to the forefront as well. So, although we’ve got a strong feminist lens that we look at eating disorders through, we know that men are also affected and that’s where equality and equity and transparency and all of that comes into play.

“For us, yes, it is about the food and it is about encouraging good nutritional intake (and the relationship with food), but we don’t purely concentrate on that number on the scale that indicates re-nourishment. It’s very important and that’s where our GPs and our psychiatrists step in.

“But for us, recovery is around … ‘my relationship with food, my relationship with my environment and connectivity to the community’ ”.

“We are about connection and … community and … that vibrant lived experience and mentors (coming) together to help create this community where people can feel safe to recover in. We try to create a space for people to have a voice … and feel connected to the community to help with recovery,” she said.

COVID-19

The rapidly evolving consequences of COVID-19 caused complications to EDQ’s community-based model. But Chelius credits her organisation’s solid policy and good governance as the reason why their transition to telehealth during the pandemic was almost seamless.

“We literally packed up in one day to move everything to telehealth. It was quite awe-inspiring to see the resilience of the team knowing that this had to happen,” she said.

“We packed up on the Monday, 23 March. (In) the morning we had a meeting, that afternoon sessions were happening. It’s a bit of blur to think that we actually did that and we didn’t lose a day of service delivery. Not one day.”

Due to Queensland’s large rural and remote communities, EDQ always had a telehealth platform for regional work but this was upgraded for working from home purposes, ticking boxes required by professional bodies to ensure safety, security and privacy.

“Groups were a bit difficult,” she said. “We went in with a bit of trepidation but the clients were keen enough to keep contact.”

Support and treatment groups moved online, were smaller and ran more frequently, with sessions held during the day instead of after hours, which resulted in less anxiety for clients.

“The practitioners were great, they did a lot of fun things on Zoom – funny hats, drawings, and breakout rooms,” she said.

At the moment, EDQ is operating in a mixed mode, with some clients coming into the office and some using telehealth, while groups are still virtual.

IMPACT ON EATING DISORDERS

Belinda said numbers for client contact (measured by at least one service received) were up by 54%, which is quite significant in terms of sessions and engagements.

Eating disorder presentations were generally much higher across Australia as a result of the pandemic, which caused a “perfect storm” of conditions, such as feelings of loss of control and the lack of normal supports.

“Our clients became very unwell, so we had a presentation of acuity – rapidly becoming unwell physically and mentally. There was this very quick decline, for want of a better word,” she said.

“Isolation is not great for an eating disorder. We know they thrive in secrecy. All the stuff that makes an eating disorder thrive, was this perfect storm during the pandemic – the isolation, the shortage of food, safe foods not being around, isolating alone or with problematic or family relationships that were uncomfortable ...

“Clients dealing with their trauma and that’s an ongoing recovery journey for them, and unfortunately I think COVID has added to that complexity of it. That’s the dynamic of it. It’s put an extra layer and probably extra length on recovery for clients.

“I’m just hoping that coming back from that hasn’t created a sense of hopelessness, and a sense of, ‘I’m back to square one’.

“That’s something we’ll just have to wait and see how it unfolds and how it impacts on people’s resilience,” she said.

TELEHEALTH

Belinda said that anecdotal feedback backed by numbers during the March/April lockdown showed contacts were up by 70% with a 50-50 take-up of telehealth.

“What that tells me … is people still used it, still wanted to do it,” she said. “There were definitely clients who would say they preferred not to do it and wanted to do face to face but those were in the minority. Once we came back in August those clients re-engaged quite quickly.

“It’s created this sort of agility and innovation that we all didn’t think was possible.”

Community connection was harder to deal with as clients could no longer pop in for lunch, sit in the library or take part in activities like art. “That little touchpoint was missing,” she said.

Trauma-informed yoga and Community Table, the group component of the meal support program, also stopped completely. “That is just not something we felt was safe to run via virtual platform. But then the client misses out on what the Community Table is about, which is connected eating, which informs their recovery,” she said.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND ZOOM

Belinda said learning to use Zoom and social media platforms was a huge learning curve for clients and practitioners alike – particularly when marking events such as World Eating Disorders Action Day (WEDAD), and Body Image & Eating Disorders Action Day (BIEDAW) and Women’s Day - usually a time to come together, contribute to collages, “wear the T-shirts” and celebrate communally.

“This time around it was all via Zoom, or via Facebook or Instagram - which people attended, absolutely, and you get big numbers - but it’s not the same,” she said.

EDQ scheduled live streams, online conversations, virtual communications, photos and posts.

“We had to up our ante,” she said. “(It was a) huge learning curve for people who are mental health professionals, used to sitting in a room and doing therapy with people, to all of a sudden we’ve got to be out there on social media and doing interviews and asking questions. That moved a lot of the workers out of their comfort zone.”

There were some welcome discoveries along the way, however.

“Early intervention and prevention doesn’t just happen in a formalised setting, like going to a school or having an event,” she said. “Social media and media is where people are at. We ran five sessions and they had over 300 views each. You just don’t get that in place-based activities.

“Because we as an organisation are so passionate about weight stigma and anti-diet culture and how do we get that message out - you’ve got to get it out where people are at, which is on social media.”

FIGHTING BIAS

“We’re a small voice and we’re a voice that’s not the norm,” she said, adding that everyone in the eating disorder field is battling diet culture and weight stigma. Her advice was to be persistent - go on radio, give interviews, have conversations, put “banners up on bridges” and enter social media campaigns.

“What we also need is the community’s conversations to stop around weight – the biases, stigma, the health indicators around that – that’s how we going to stop some (eating disorders and disordered eating), not all - if the community can just commit to the right conversation.”

INDIGENOUS MODEL BEHIND PEER SUPPORT PROGRAM

The Peer Support Program and mentoring is an important part of EDQ, which Belinda said was based on an Indigenous program that had been adapted for eating disorders. The pilot ran in 2012, was trialled for six months in 2013 and has played a role ever since.

“Our Peer Support model is very much based on an Indigenous Peer Support model. We didn’t invent the model,” she said.

She said storytelling was core to the narrative approach that Indigenous communities take and encompassed Big Sister/Big Brother programs, with an Elder, leader or mentor to walk alongside a person, show the way, show different paths and what worked for them.

“How to manage their own recovery with their own strengths,” she said.

EDQ has stuck to the model but over the years has increased training for mentors, ensuring they are well supported and that their recovery stays as stable as possible.

REACHING OUT

Organisations need to be accessible to form relationships with marginalised groups, Belinda said, with a physical presence in an office and visual signs, such as flags and messaging to show welcome and the availability of equitable services to all. Rural, Indigenous and LGBTIQ communities needed to be prioritised, with care taken about cultural sensitivities.

“(For) some communities it is not in their culture to talk about eating disorders,” she said, noting work underway to create a good relationship with groups working with young Indigenous mothers with eating disorders. “We make sure we’re present at NAIDOC – be there and have those conversations and make those connections.

“We’ve always had a very strong connection and openness to the LGBTIQ community,” she said. “But there’s definitely work to be done.”

Belinda is a skilled, dedicated, culturally sensitive and passionate feminist senior social work clinician, who holds a BA (Health Sc & Soc. Services), MSocWK degree and the role of general manager of Eating Disorders Queensland. She has practiced in the field of complex mental health, dual-diagnosis (alcohol and or other drugs); trauma (sexual assault, domestic violence) and eating disorders for over 20 years in the not-for-profit sector.

Belinda is experienced in leading teams in these complex areas, navigating ethical and service delivery issues in a proactive and creative way within the boundaries of service and funding agreements and AASW practice standards. A natural progression of her career has been to move into a broader systems reform practice, pinpointing service delivery gaps for clients and implementing reform initiatives. She has achieved this due to a strong natural ability to connect with various inter-disciplinary sectors and has developed substantial interagency connections, with links across the NGO sector, public mental health sector and primary health care.

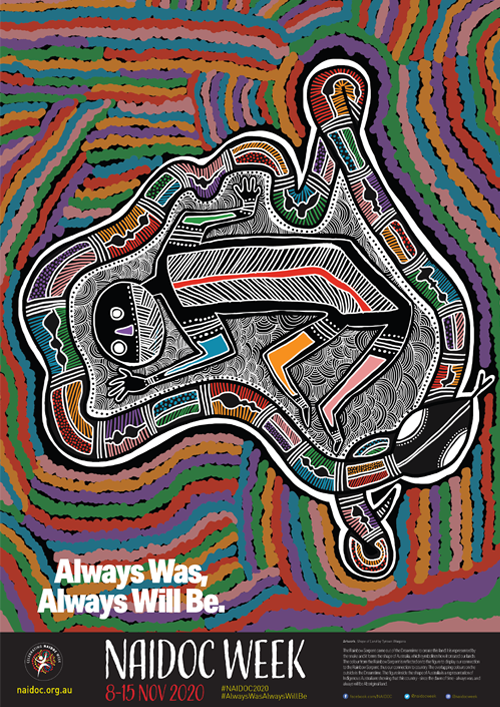

The 2020 National NAIDOC Poster, Shape of Land, was designed by Tyrown Waigana, a Noongar and Saibai Islander man.

Tyrown’s artwork tells the story of how the Rainbow Serpent came out of the Dreamtime to create this land. It is represented by the snake and it forms the shape of Australia, which symbolises how it created our lands. The colour from the Rainbow Serpent is reflected on to the figure to display our connection to the Rainbow Serpent, thus our connection to country. The overlapping colours on the outside is the Dreamtime. The figure inside the shape of Australia is a representation of Indigenous Australians showing that this country - since the dawn of time - Always Was, Always Will Be Aboriginal Land.

Marking NAIDOC Week

Each year, NAIDOC Week celebrations are held across Australia to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC Week 2020 ran from the 8th to 15th November, with the theme "Always Was, Always Will Be". This theme recognises that First Nations peoples have occupied and cared for this continent for over 65,000 years (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). NEDC recognises this rich history of spiritual and cultural connection to land, and that sovereignty was never ceded.

While research into the prevalence of eating disorders among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is limited, recent studies suggest that prevalence of eating disorders may be equal (Mulder-Jones et al., 2017) or higher (Burt et al., 2020) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than among non-Indigenous Australians.

It is essential that the eating disorders sector listens to and learns from the knowledge and expertise of First Nations organisations, leaders and clinicians, as well as the lived experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with eating disorders, and their carers and supports.

We all have a responsibility to ensure that the system of care for eating disorders in Australia is accessible, culturally responsive and safe for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In particular, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ concept of social and emotional wellbeing must be understood and valued (Dudgeon et al., 2014). The NEDC will be listening to the voices and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and will be working collaboratively to help build a culturally safe system of care for eating disorders in Australia.

References:

Burt, A., Mannan, H., Touyz, S., & Hay, P. (2020). Prevalence of DSM-5 diagnostic threshold eating disorders and features amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples (First Australians). BMC Psychiatry, 20(449). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02852-1

Commonwealth of Australia. (2020). 2020 theme. https://www.naidoc.org.au/get-involved/2020-theme

Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., & Walker, R. (2014). Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice (second edition). Australian Government Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/working-together-aboriginal-and-wellbeing-2014.pdf

Mulders-Jones, B., Mitchison, D., Girosi, F., & Hay, P. (2017). Socioeconomic Correlates of Eating Disorder Symptoms in an Australian Population-Based Sample. PloS One, 12(1), e0170603. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170603

Louise Dougherty is NEDC’s Primary Health Project Manager. She has a public health research background and has led a number of applied research projects on systems change, with a particular focus on improving access to healthcare and reducing health inequities. She has previously held research positions at the University of New South Wales and Sydney Local Health District. She is passionate about contributing to the development of an equitable and accessible system of care for the prevention and treatment of eating disorders for all Australians.

« Back to Browse Resources