Binge eating disorder (BED)

Any person, at any stage of their life, can experience an eating disorder. More than one million Australians are currently living with an eating disorder (1).

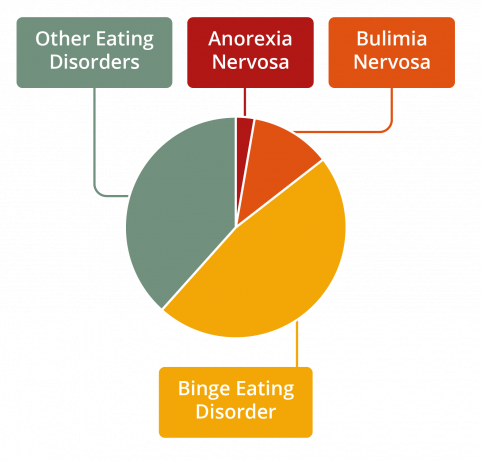

Of people with eating disorders, 47% have binge eating disorder compared to 3% with anorexia nervosa, 12% with bulimia nervosa and 38% with other eating disorders (1). Of people with BED, just over half (57%) are female (2).

Eating disorders are not a choice but are serious mental illnesses. Eating disorders can have significant impacts on all aspects of a person’s life – physical, emotional and social. The earlier an eating disorder is identified, and a person can access treatment, the greater the opportunity for recovery or improved quality of life.

Figure 1. Prevalence of eating disorders by diagnosis

What is BED?

A person with BED will experience a sense of lack of control and will eat a large amount of food within a relatively short period of time. Binge eating often evokes feelings of guilt and shame, and a person binge eating may eat alone or be secretive about their eating habits.

BED is a serious mental illness. BED is characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating, which involves eating a large amount of food in a short period of time. During a binge episode, the person feels unable to stop themselves eating, and it is often linked with high levels of distress. A person with BED will not use compensatory behaviours, such as self-induced vomiting or overexercising after binge eating.

The reasons for developing BED will differ from person to person; known causes include genetic predisposition and a combination of environmental, social, and cultural factors. BED can occur in people of all ages and genders, across all socioeconomic groups, and from any cultural background. Large population studies suggest that equal numbers of males and females experience BED.

Characteristics of BED

Frequent episodes of binge eating

A person with BED will recurrently engage in binge eating episodes where they eat a large amount of food in a short period of time, usually less than two hours. To meet diagnostic criteria for BED, the binge eating episodes occur at least once a week for three months. During these episodes, the person will feel a loss of control over their eating and may not be able to stop even if they want to.

Eating habits

A person with BED will often have a range of identifiable eating habits. These can include eating very quickly, eating when not physically hungry and continuing to eat even when full or feeling uncomfortable.

Feelings around food

Feelings of guilt and shame are highly prevalent in people with BED. People with BED often feel guilty or ashamed about the amount and the way they eat during a binge eating episode. Binge eating often occurs at times of stress, anger, boredom, loneliness or distress. At such times, binge eating is used as a way to cope with or distract from challenging emotions. The person may experience feelings of guilt, shame, disgust, and depression after the episode of binge eating.

A person’s feelings about their body, weight and shape can also trigger someone to binge eat. For example, someone might break a ‘diet rule’, they might feel full, or they may feel extremely hungry due to dieting.

Behaviours around food

Because of their feelings around food, people with BED are often very secretive about their eating habits and choose to eat alone.

Risk factors

The elements that contribute to the development of BED are complex, and involve a range of biological, psychological and sociocultural factors. Any person, at any stage of their life, is at risk of developing an eating disorder. An eating disorder is a mental illness, not a choice that someone

has made.

Dieting is a risk factor for the development of BED, as well as other eating disorders. The associated feelings of hunger, or the resulting feelings of failure and guilt if a ‘diet rule’ has been broken, can both trigger binge eating. For these reasons, eating regular and satisfying meals are important to prevent the physiological and psychological responses that can lead to binge eating.

Find out more about the risk factors for eating disorders in the Disordered Eating and Dieting Fact Sheet.

Warning signs

The warning signs of BED can be physical, psychological and behavioural. It is possible for someone with BED to display a combination of these symptoms, or no obvious symptoms.

Physical

• Feeling tired and not sleeping well

• Changes in weight

• Feeling bloated, constipated or developing intolerances to food

Psychological

• Preoccupation with eating, food, body shape and weight

• Body dissatisfaction and shame about their appearance

• Feelings of extreme distress, sadness, anxiety and guilt during and after a binge eating episode

• Low self-esteem

• Increased sensitivity to comments relating to food, weight, body shape, exercise

• Depression, anxiety, self-harm or suicidality

Behavioural

• Evidence of binge eating such as disappearance or hoarding of food

• Secretive behaviour around food such as not wanting to eat around others

• Evading questions about eating and weight

• Increased isolation and withdrawal from activities previously enjoyed

• Erratic behaviour such as shoplifting food or spending large amounts of money on food

It is never advised to ‘watch and wait’. If you or someone you know may be experiencing an eating disorder, accessing support and treatment is important. Early intervention is key to improved health and quality of life outcomes.

Impacts and complications

Ongoing binge eating can result in medical and psychological consequences (3).

Medical

Some of the medical impacts and complications associated with BED include:

• Cardiovascular disease

• Type 2 diabetes

• High blood pressure and/or high cholesterol leading to increased risk of stroke, diabetes and heart disease

• Osteoarthritis: a painful form of degenerative arthritis in which a person’s joints degrade in quality and can lead to loss of cartilage

• Chronic kidney problems or kidney failure

Psychological

Some of the psychological impacts and complications associated with BED include:

• Extreme body dissatisfaction/distorted body image

• Social withdrawal or isolation

• Feelings of shame, guilt and self-loathing

• Depressive or anxious symptoms and behaviours

• Self-harm or suicidality

Treatment options

Access to evidence-based treatment has been shown to reduce the severity, duration and impact of BED.

The goals for treatment of BED are to reduce binge eating and to support the person to eat regular meals. Addressing other related emotional factors such as anxiety, depression, and self-esteem is also important.

The research indicates that a number of psychological therapies are effective in the treatment of BED. These include:

• Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Enhanced (CBT-E)

• Cognitive Behaviour Therapy – Guided Self Help (CBT-GSH)

• Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) (4)

Most people can recover from an eating disorder with community-based treatment. In the community, the minimum treatment team includes a medical practitioner such as a GP and a mental health professional.

Inpatient treatment may be required when a person needs medical and/or psychiatric stabilisation, nutritional rehabilitation and/or more intensive treatment and support.

Other treatments

There is some evidence for the use of anti-depressants (SSRIs) to treat BED (5). If required, these other treatments are recommended alongside psychological treatment (5).

Recovery

It is possible to recover from BED, even if a person has been living with the illness for many years. The path to recovery can be long and challenging, however, with the right team and support, recovery is possible. Some people may find that recovery brings new understanding, insights and skills.

Getting help

If you suspect that you or someone you know may have BED, it is important to seek help immediately. The earlier you seek help the closer you are to recovery. Your GP is a good ‘first base’ to seek support and access eating disorder treatment.

To find help in your local area go to NEDC Support and Services.

Download the binge eating disorder fact sheet here.

References

1. Deloitte Access Economics. Paying the price: the economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. Australia: Deloitte Access Economics; 2012.

2. Hay P, Girosi F, Mond J. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian population. J Eat Disord. 2015;3(1):1-7.

3. Sheehan DV, Herman BK. The psychological and medical factors associated with untreated binge eating disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord.

2015;17(2).

4. Heruc G, Hurst K, Casey A, Fleming K, Freeman J, Fursland A, et al. ANZAED eating disorder treatment principles and general clinical practice and training standards. J Eat Disord. 2020;8(1):63.

5. Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, Madden S, Newton R, Sugenor L, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(11):977-1008.